What soil for the Alsatian vineyard? The Alsace vineyard is situated on an unparalleled mosaic of soils. Alsatian geology is of rare complexity: it features a patchwork of rocks ranging from granite to limestone, including clay, schist, or sandstone. This great diversity – across a vineyard of approximately 15,500 ha – creates a favorable environment for the “flourishing of many grape varieties and gives Alsace wines an extra soul”, both unique and complex.

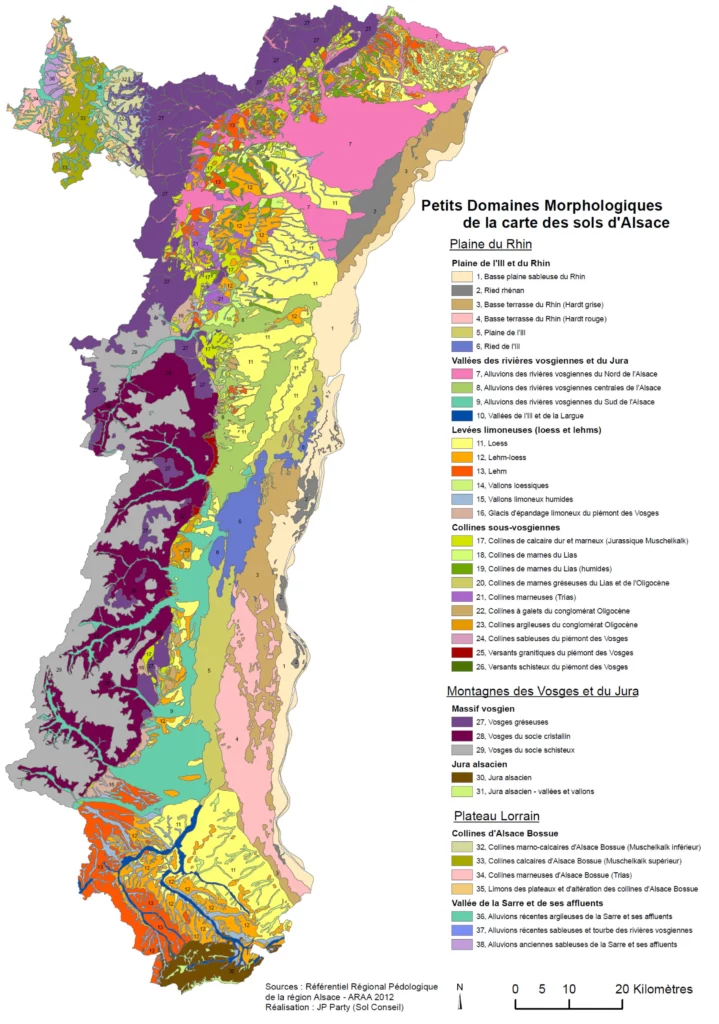

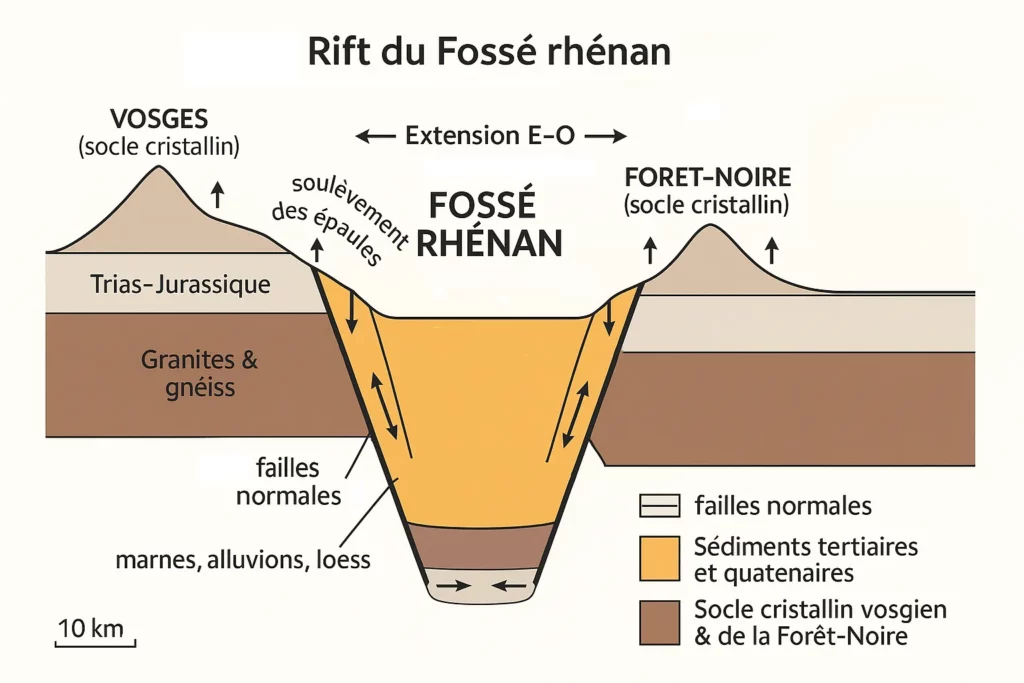

This exceptional diversity is explained by a turbulent tectonic history. Millions of years ago, the Earth’s crust subsided, forming the Rhine Graben (rift) between the Vosges and the Black Forest. Multiple collapses and faults fragmented the subsoil into a multitude of blocks, exposing almost all geological strata from the primary to the Quaternary periods. Thus, the crystalline Vosges bedrock (granites, gneiss, schists) coexists with varied sedimentary deposits (limestones, marls, sandstones, conglomerates) in the sub-Vosgian hills, while the plain of Alsace is covered with marls, fluvial alluvium, and glacial loess. Four large fault zones (Saverne, Ribeauvillé, Rouffach-Guebwiller, and Thann) further divide the vineyard into geological sub-regions.

Furthermore, the nature of the soil directly influences the vine: it determines the depth of the root network and the plant’s access to water and nutrients. For example, a light, sandy, very porous soil drains water quickly (avoiding excess humidity), while a clayey soil will tend to do the opposite, retaining water and staying cool longer. Limestone, for its part, provides essential mineral elements to the vine. These soil differences ultimately translate into the grape and thus into the wine: they modulate the vine’s maturity and vigor, and contribute to the wine’s aromatic and structural personality. It is not easy to isolate the exact role of the soil, as many factors are involved (climate, grape variety, viticulture…), but clear correlations are observed between certain soil types and the resulting wine style. So, what are the main soil types of the Alsatian vineyard, and what do they bring to the wines? Let’s look at this in detail.

The Main Soil Types of the Alsatian Vineyard

Thanks to geological studies (notably those by Claude Sittler), no fewer than 13 categories of wine-growing soils are distinguished in Alsace. Each possesses specific physical and chemical characteristics that influence the style of the wines. They can be grouped into three major morphological sets: Vosges mountain soils (hard primary rocks, thin soils), sub-Vosgian hill soils (varied secondary and tertiary deposits), and plain soils (recent Quaternary deposits). Here is an overview of the main types of Alsatian terroirs and their effects on the vine and wine:

Focus on our Emblematic Alsatian Terroirs: Scherwiller, Rittersberg, Ortenberg

To concretely illustrate the influence of Alsatian soils on wine, let’s look at three terroirs located around the commune of Scherwiller (Central Alsace, Bas-Rhin). Within a few kilometers, one finds on the one hand the alluvial cone of Scherwiller in the plain, and on the other hand two neighboring granitic slopes: the Rittersberg and the Ortenberg, at the foot of Ortenbourg Castle. These three locations, notably exploited by our estate, show how very different soils (alluvial gravels vs. granite) give rise to wines with distinct profiles, even with the same grape variety (often Riesling on these terroirs).

Scherwiller: Giessen Alluvium

Scherwiller is a wine-growing village built on the alluvial fan of the Giessen river, at the mouth of the Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines valley. Its vineyard is classified as Appellation Communale Scherwiller (one of the rare geographical designations in Alsace), reserved exclusively for Riesling. The soil there consists of “very stony Quaternary alluvium: many siliceous pebbles and gravel, mixed with sand and a little silt. This light, filtering, warm, and dry soil is considered very early: the vines start quickly in spring, and the grapes reach excellent ripeness. Furthermore, the clay and limestone content is low, which favors wines with elegance.”

The Scherwiller Riesling is renowned for its minerality and fine fruitiness. Thanks to these sandy-silty gravels, it expresses a unique minerality and aromatic complexity typical of this appellation. On the nose, one often detects a very appealing muscat aroma (pome fruits, fresh grape), with nuances of citrus and white flowers. On the palate, the wine is crisp and fresh, with well-integrated acidity and a delicately lemony finish. It is a dry, elegant Riesling that offers a balance between aromatic finesse and freshness. It pairs wonderfully with seafood, grilled fish, or Alsatian specialties (sauerkraut) due to its refreshing quality. This wine is best enjoyed within 3 to 5 years to fully appreciate its aromatic explosion.

The Rittersberg: an Exceptional Granitic Hillside

The Rittersberg (literally “”knights’ mountain””) is a lieu-dit situated on the slopes just southwest of Scherwiller, towards the Vosges, dominated by the ruins of Ortenbourg Castle. It is a granitic hillside classified as a specific lieu-dit, long known for the quality of its wines. The soil of Rittersberg comes from a very old two-mica granite, which has deeply weathered, forming sandy granitic arena. Peculiarity: the soil layer there is very thin in places – the rock quickly outcrops. This shallow soil depth means that the vine must root deep into the rocky substrate and naturally suffers from water stress in summer (dry soil). The vine “”eats little”” on this poor soil, yielding small, concentrated bunches.

Rittersberg yields wines with intense minerality, often marked by a salinity on the finish (a slight saline taste that enhances the tasting). The king grape variety on this soil is Riesling: it develops fine aromas of acacia, linden, with distinguished mineral notes. On the palate, Rittersberg Riesling is ample, well-structured, with good body and notable persistence. One feels a lively, ripe acidity that carries the finish far. These are wines made for gastronomy and aging: their solid structure allows them to refine further after a few years in bottle. Rittersberg also produces excellent Pinot Noirs (reds) with fine tannins and vibrant fruitiness, and Pinot Gris and Gewurztraminers with good tension. In short, this granitic hillside yields aristocratic wines, both powerful and elegant, among the most prized in Bas-Rhin.

The Ortenberg: Deep Granite

Near Rittersberg is another highly reputed lieu-dit: the Ortenberg. It is also a granitic terroir, located on a neighboring hillside (facing more to the east), but which presents a major difference: here the granite is covered by a deeper soil layer, richer in fine sand and silts. In other words, Ortenberg is a granite that is a bit more weathered and filled in: the bedrock is fractured deep down, forming granitic scree mixed with coarse sand over several tens of centimeters. This soil retains water a little better than Rittersberg and offers easier rooting. The vine suffers less from drought there, which translates into more regular ripeness and slightly higher yields.

The Ortenberg wines are distinguished by aromas of great fruity intensity. This granitic terroir “”with deeper subsoil”” yields wines with intense fruit aromas (ripe fruits, exotic fruits), while retaining a mineral framework. The flagship grape variety on this hillside is Pinot Gris: it acquires a rich aromatic palette (well-ripened yellow fruits, smoky note, sweet spices) and a round, generous palate with good length. We highlight the Pinot Gris Ortenberg as a wine of great elegance, a true expression of granite, with complex smoky aromas and a persistent finish. On the palate, there is an indulgent richness balanced by a pronounced minerality that brings freshness. This wine pairs wonderfully with refined dishes such as foie gras or braised white meats. The Riesling cultivated on Ortenberg also develops a more exotic fruity character than on Rittersberg, with slightly less biting acidity, which makes it accessible earlier. One can therefore say that Ortenberg offers the generous and aromatic side of granite, while Rittersberg is its strict and mineral side – two complementary facets of the Scherwiller terroir.

Granitic (and Gneissic) Soils

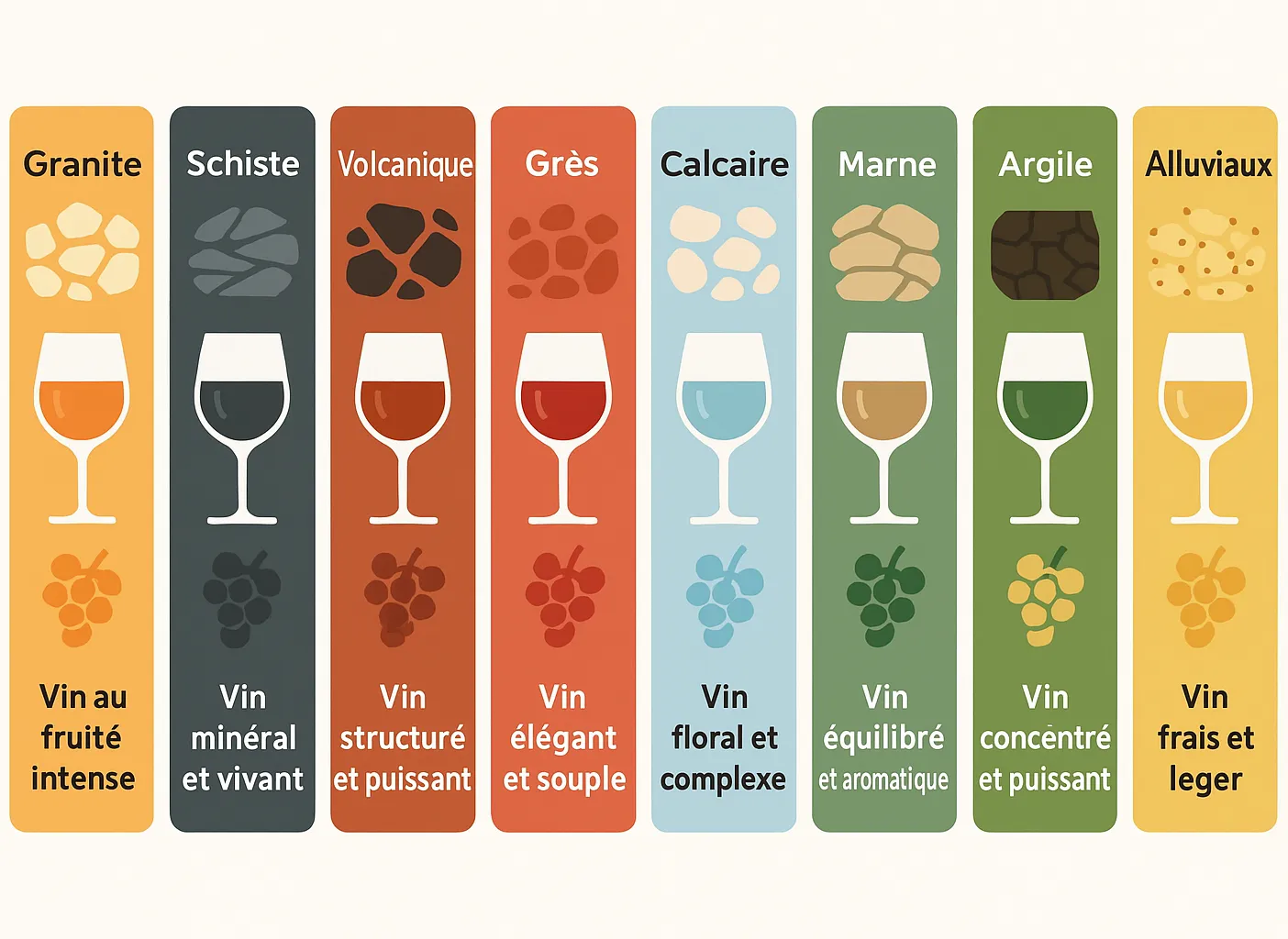

Granitic terroirs occupy the slopes of the Vosges, on the ancient crystalline bedrock. Granite is a hard, fractured magmatic rock that disintegrates, producing a coarse sand called granitic arena. These very stony soils, with low water retention, are poor in clay and humus. Their fertility depends on the degree of granite alteration: the more it is decomposed (into sands and silts), the more mineral elements become available for the vine. Chemically, these are acidic soils (rich in silica, poor in limestone).

Vines planted on granite often have to plunge their roots deep into the rock’s fissures to find water, which naturally limits their vigor. This results in moderate yields and good grape ripeness. Wines from granitic soils are renowned for their aromatic finesse and floral/fruity expression, with much “brilliance in their youth. The palate structure is generally light to medium, supported by a lively and elegant acidity. They are often appreciated in their youth for their expressiveness, although the best of them can age. Notably, the abundant presence of quartz (silica crystals) in granite is believed to contribute an additional touch of liveliness and acidity to the wines. Example: the Grand Cru Frankstein in Dambach-la-Ville, on two-mica granite, yields chiseled, intense, and very mineral Rieslings, which well illustrate the elegance of granitic terroirs.”

Schist Soils

In Alsace, schist outcrops are quite rare: they are found mainly in the Andlau region (Bas-Rhin) and near Villé, where primary era schists outcrop on the edge of the Vosges. These schist soils are generally rich in fertilizing elements (they are transformed clays), relatively deep, and well-drained by the schist fissures. They also store solar heat well.

Wines from schist terroirs are characterized by a certain acidic power and straightness on the palate, with a nervous and racy side. They often develop a marked minerality (stony, smoky notes) and gain complexity with time. Indeed, these wines are said to be slow to open up: often closed and austere in their youth, they require a few years of aging to reveal their full potential. These are wines of longevity. Example: the Grand Cru Kastelberg in Andlau (the only Grand Cru on black schists) produces very taut Rieslings, austere in their early years.

Volcanic Soils

These terroirs come from ancient Permian volcanic rocks (approximately 300 million years old) that formed through the consolidation of lava and ash in an aquatic environment. They are sometimes called volcano-sedimentary terroirs, because the lava was often mixed with deposits. The typical Alsatian volcanic rock is a compact, hard, dark basaltic tuff, which is difficult to disintegrate. Soils derived from these rocks are stony, rich in ferrous elements, and dark in color. They retain solar heat very well, which promotes grape ripening, especially in cool areas. These plots are often very steep.

Wines from volcanic terroir are renowned for their powerful and spicy character. One frequently finds smoky or grilled aromas (gunflint, flint, smoke) that reflect the basaltic soil. The palate is full, ample, and well-built, with a solid acidic structure that ensures long aging potential. These wines combine richness and vibrancy. Example: the Grand Cru Rangen in Thann, in southern Alsace, is the only Grand Cru on 100% volcanic soil (submarine volcanic tuff). It produces Rieslings and Pinot Gris of extraordinary expression: an intensely smoky bouquet, notes of candied citrus and stone, a massive palate balanced by high acidity, making them true aging wines among the most prestigious in Alsace.

Sandstone Soils (Sands and Sandstones)

Vosges sandstone is a sedimentary rock composed of cemented quartz grains (by silica or limestone, depending on the case). It is the famous “”pink sandstone”” of the Vosges, formed during the Triassic period. Geologically, sandstone terroirs are close to granitic terroirs: they are acidic, sandy, very filtering, and poor in nutrients. However, their viticultural expression is slightly different due to the finer sand texture and lower mineralization. Sandstone soils are light, often shallow, sometimes covered by forests (they were cleared for vines on certain well-exposed hillsides).

Sandstone wines generally exhibit a particularly lively and persistent acidity – we speak of a longer acidic backbone. In contrast, the aromatic profile is often more discreet in their youth compared to granite or marl wines: fruity/floral aromas take longer to express themselves, and the wine can seem austere or neutral in its early years. After a few years in the bottle, these wines gain aromatic complexity (floral notes, sweet spices) and retain great freshness. In short, sandstone terroirs produce wines built for cellaring, which need time to reveal their elegance. Example: the Grand Cru Kirchberg de Barr (Lower Rhine) is partly sandstone: it yields Rieslings that are very straight and taut in their youth, which after 5 years develop beautiful notes of dried herbs and candied citrus, all while maintaining structuring freshness.

Limestone Soils

Alsace’s limestone terroirs originate from marine sedimentary rocks (Triassic, Jurassic seas, etc.) dating back to the Secondary era. These limestone rocks, as they fragment, yield very stony soils, but with a sometimes significant fine clay fraction. Chemically, these are basic soils (alkaline, rich in calcium carbonates) that buffer acidity. They generally have good water retention capacity in clayey areas, while remaining well-drained thanks to the stones.

Limestone terroir wines almost always have a solid and broad acidic structure – paradoxically, despite the basic pH of the soil, the vine exalts a generous and taut acidity in the wine, a guarantee of longevity. These wines are distinguished by their ample body on the palate, with substance and power, but also an austere side in their youth. Indeed, white wines from limestone are often aromatically closed when young, appearing reserved, almost strict. Furthermore, limestone soils have a reputation for producing wines with a more mellow and generous texture once settled, perhaps due to a less lively pH and a nutrient supply favorable to good ripeness. Example: on the Grand Cru Osterberg in Ribeauvillé (Muschelkalk limestone), Riesling yields a very straight and tight wine when young, which softens with time.

Marl-limestone Soils (Clay-Limestone)

Many Alsatian hillsides are formed of marls (calcareous clays) mixed with limestone pebbles. Through erosion and rockfalls from the cliffs, these elements form thick layers of deposits known as marl-limestone or conglomerates. The bedrock evolves slowly and subtly there, forming deep, heavy soils with a high proportion of clay and fragmented limestone. These clay-limestone soils have a high water retention capacity (thanks to the clay) while remaining sufficiently draining (thanks to the limestone gravel): an ideal balance for the vine, which finds both freshness in summer and moderate water stress.

Wines from marl-limestone theoretically combine the best of both components: the power and richness provided by the marl, supported by the beautiful long acidity conferred by the limestone. When young, these wines are often generous, ample, and long on the palate, with volume and a rich aromatic palette (ripe fruits, spices, sometimes a smoky touch). They age admirably well, gaining minerality (stone notes, petrol for Riesling) and complexity over decades. The greater the proportion of limestone in the soil compared to clay, the more the wine will develop finesse and tension as it ages. Conversely, a very clayey marl-limestone will yield a more opulent and aromatic wine in its youth. This type of balanced terroir is particularly suitable for rich grape varieties like Pinot Gris or Gewurztraminer, which acquire structure and aging potential there. Example: the Grand Cru Hengst in Wintzenheim, a heavy marl-limestone terroir, produces spicy, very powerful, and alcoholic Gewurztraminers in their youth, but which after 15 years transform into complex wines of great elegance, with notes of truffle and candied fruits.

Mixed Marl-Sandstone, Marl-Limestone-Sandstone Soils, etc.

In the sub-Vosgian hills, many terroirs feature a mixture of several rocks. The most frequent combinations associate marly elements (clay) with sandstone (sand) and/or limestone elements. These composite soils often originate from varied Tertiary scree. For example, a marl-sandstone terroir is the “sandstone” variant of marl-limestone: there are sandstone pebbles instead of limestone in the clay matrix. This mixture creates a soil with a dual effect: the marl brings power and body to the wine, while the sandstone lightens the structure and provides a lively acidity. Wines from marl-sandstone often prove more generous than on pure sandstone (less austere) and with more complex aromas than on pure marl. An interesting compromise between richness and finesse is achieved.

There are also marl-limestone-sandstone terroirs mixing clay, limestone, and sandstone in the soil. These deep and very mineral-rich lands combine the effects of the three components: the vigor and structure provided by the marl, balanced by the lightening action of limestone and sandstone. However, the wine’s harmony may take time: these wines often take longer to integrate their antagonistic components and find their balance. Finally, let’s mention the rare limestone-sandstone terroirs (quartz cemented by limestone): the rock there is very hard and alters little, producing an extremely stony and poor soil. Limestone-sandstone wines are described as very taut, straight on the acid, with intense floral expressions. Their minerality is marked, almost sharp, and they often require several years of aging to soften.

Heavy Clay and Marl Soils (Clay-Marl)

Certain sectors of the vineyard (often at the bottom of slopes or on plateaus) have soils that are almost exclusively clayey or marly, without many stones. Pure clay forms soft but compact rocks, yielding heavy, sticky, and greasy soils when wet. These clay-marl soils have high chemical fertility, as clay strongly retains nutritive cations (potassium, magnesium, etc.) and makes them available to the roots. In return, they can suffer from waterlogging (slower drainage) and cool down quickly in depth. The vine grows vigorously there but may struggle to ripen perfectly if the soil is too rich and humid.

Wines from heavy clay soils are distinguished by a robust structure and a great mouthfeel. These are often very powerful wines, which require time to open up. When young, they can seem a bit rustic or harsh, with a bitterness or even a slight astringency unusual for white wines. This tannin sensation comes from the strong extraction of matter in the grape when the vine grows on clay (thicker skins, polyphenol richness). After a few years of aging, these wines become more integrated and can develop opulent tertiary aromas (honey, dried fruits, spices). Clay terroirs are well suited to the most aromatic and opulent Alsatian grape varieties: Gewurztraminer, in particular, thrives there, yielding very full-bodied wines, and Pinot Gris can acquire a rich, almost luscious texture in late harvests.

Colluvial and Piedmont Soils

At the bottom of hillsides and at the mouth of the Vosges valleys, one finds alluvial fans and slope-foot deposits called colluvium. These are materials torn from the slopes by the “erosion (scree, gravel, silts) and accumulated during the Quaternary period”. The mineralogical composition of these colluvium depends directly on the rocks present upstream: it can therefore vary enormously from one place to another. For example, an alluvial fan from a granitic valley will be mainly acidic sandy-gravelly, while one from a marly valley will be silty and calcareous. The fertility and water retention capacity of these soils depend on this composition.

Wines from colluvium do not have a uniform profile due to this variability. On light colluvium (e.g., siliceous scree), one will obtain wines that are rather lively, aromatic, and to be drunk in their youth. On heavy clayey colluvium, the wines can be more powerful and suitable for aging. Generally, piedmont terroirs offer wines of an intermediate style between those of the mountains and the plains.

Alluvial Plain Soils

The Alsace plain, between the wine route and the Rhine, features alluvial terraces deposited by watercourses over millennia. These alluvial soils consist of sands, silts, gravels, and rounded pebbles, brought and then sorted by rivers. The materials are rolled (smoothed surface) and classified by size: pebbles and gravels form very draining layers, while silts form finer layers that retain water better. Depending on the history of the watercourses, the proportion of pebbles, sand, or silt varies from one area to another. Overall, these are light, warm, and filtering soils, often poor in nutrients. They warm up quickly in spring, which makes them early-ripening terroirs for the vine.

Wines from alluvium are generally marked by freshness and minerality. These terroirs yield wines with often intense floral and fruity aromas, sometimes with slightly muscat or spicy notes, and a supple, thirst-quenching palate. Thanks to the deep and draining soils, the vine develops an extensive root system there, which can lead to relatively high yields – hence wines that are often pleasant to drink young, less concentrated than those from hillsides. Indeed, it is recommended to enjoy the aromatic purity of these wines in their early youth, before the acidity declines. Example: plain Rieslings (e.g., communal appellation Klevner de Heiligenstein or Riesling de Scherwiller) are renowned for their expressive bouquet and suppleness, to be enjoyed within 3 to 5 years. Conversely, on certain stonier and poorer terraces, very mineral, chiseled white wines can be obtained, reminiscent of the tension of mountain terroirs. Scherwiller is an emblematic case of a gravelly alluvial terroir producing a dry Riesling of beautiful minerality – we will discuss this further later.

Loess Soils (Aeolian Silts)

Loess is another plain soil very present in Alsace. It is a deposit of fine sediments (silts) brought by the wind during the Quaternary glaciations. This yellowish, very homogeneous silt has accumulated in layers sometimes several meters thick, especially in central and northern Alsace. Pure loess is loose and highly fertile (rich in fine limestone, clay, and leached minerals). Over time, loess transforms into more clayey loam through leaching. Loess soils are deep, easy to work, and retain water moderately. They sometimes cover other terroirs, forming a uniform silty mantle.

Loess wines generally present a charming and delicate aromatic profile. These are often wines quite soft on the palate, with moderate acidity and a beautiful roundness. They feature floral aromas (linden, hawthorn) and white-fleshed fruits. Their minerality is less pronounced than on pebbles or hard rocks, but they retain a certain freshness. These wines are also best enjoyed in their youth, to fully appreciate their pure fruitiness. Many Alsace Muscat, Pinot Blanc, or Sylvaner wines come from loess parcels, yielding light, convivial, and easy-to-drink wines. Of course, if the loess is merely a covering over a limestone subsoil, the wine can combine the finesse of the loess with the structure of the underlying limestone. In short, loess brings a silky texture and an accessible side to wines, without heaviness.

| Soil Type | Characteristics (Soil) | Typical Impact on Wine |

|---|---|---|

| Granitic soil (arena) | Coarse acidic sand, very draining, poor. | Expressive, lively, light wines, to be drunk young. |

| Schist soil | Layered rock, rich in minerals, retains heat. | Racy, fresh wines, closed when young, slow to open. |

| Volcanic soil | Dark stones, retain heat, difficult to alter. | Smoky, ample, very structured wines, for long aging. |

| Sandstone soil (sand/sandstone) | Hard quartz sand, acidic, very filtering. | Wines with high acidity, discreet aromas when young, aging required. |

| Limestone soil | Basic scree, alkaline stony soil. | Wines with broad acidity, massive body, closed when young then lemony. |

| Marl-limestone soil | Clay + limestone, heavy and water-fertile soil. | Powerful wines, long on the palate, which mineralize with age. |

| Heavy clay soil | Pure clay, greasy soil, very fertile in minerals. | Very rich, structured wines, sometimes bitter/tannic when young. |

| Alluvial soil (pebbles) | Pebbles, gravel, sands in the plain, very draining. | Mineral, floral, fresh wines, to be drunk in their youth. |

| Loess soil (silt) | Fine aeolian silt, fertile, deep, calcareous. | Supple, aromatic, low-acid wines, to be enjoyed young. |

Ultimately, Alsace benefits from an incredibly diverse geological heritage which, combined with the variety of grape varieties and microclimates, results in an unparalleled range of wines. The notion of terroir takes on its full meaning here: each type of soil adds its touch – vibrant acidity from granite, opulence from clay, finesse from limestone, fruitiness from alluvium, etc. The diversity of soils in the Alsatian vineyard is such that there is something for every taste: from the lightest and most floral wine to the most powerful and spicy, the Alsatian terroir is an infinite source of inspiration for those who know how to read it in the glass. Each bottle then becomes the expression of a precise place, a plot of land, extending into the wine the singular voice of the soil from which it originates.

How Does Soil Depth Affect Wine Acidity?

A thin soil (Rittersberg) imposes rapid water stress; the plant slows its photosynthesis and concentrates acids. A deep and cool soil (loess or marl-limestone) dampens this stress; acidity remains high but better integrated, with more flesh around the structure.

Is Soil Alone Enough to Predict the Aging Potential of an Alsatian Wine?

Not entirely: grape variety, vintage, and viticultural practices also matter. Nevertheless, it is observed that wines from limestone, schist, or volcanic tectites readily age 10-20 years, while those born on alluvium or loess often show their best within the first decade.

Does the Soil Influence the Final Color of Alsace Wines?

Indirectly, yes. On heavy clays and marls, grape skins thicken, and pressing and maceration release more phenolic compounds, sometimes resulting in more golden whites or more intense rosés. On granites and filtering sandstones, the juices often remain paler and more crystalline.

Do Climate Changes Alter the Impact of Soils on Grapevines?

Yes. With hotter and drier summers, deep and clayey soils become valuable for their water reserves, whereas granites and filtering sandstones can accentuate water stress. Some estates are therefore replanting late-ripening grape varieties (Riesling, Sylvaner) on light hillsides and reserving the clays for earlier-ripening Pinot Noirs.

Sources and further information: